Armandino Liberti, poesia e voce di un’utopia proletaria

(Pop)ular A book/CD, Noi de borgata, for the first release of the new series in the I giorni cantati collection

by Alessandro Portelli – il manifesto

In the last ten lines of his supplement to the reissue of Giuseppe Micheli’s monumental (627-page) Storia della canzone romana (Newton Compton, 2005), Gianni Borgna acknowledges the existence of Armandino Liberti. Together with another of the pillars of the history of the Circolo Gianni Bosio, Silvano “Cicala” Spinetti di Genzano, he exorcises him by placing him in the category he calls “post-song”: a song that goes “beyond the limits imposed by the recording industry” but cannot be called “popular” precisely because it is difficult for the people to know and make it their own, precisely because, as Gramsci would have said, it ‘conforms to their way of thinking and feeling’ .

Much has happened since Borgna wrote those somewhat paternalistic lines, and Roman songs have had a life and growth that was unthinkable at the time. But it is right that the history of Roman songs, if it does not end with Armandino Liberti, at least stops off at him and finds further strength in listening to him. Now, beyond labels – “post-song”, ‘popular’ – Borgna was right about two things: Armandino Liberti’s songs remained unknown to the musical public and, above all, they “conform to the way of thinking and feeling” of the popular world precisely because Armandino belonged to that world and in all his songs he strove both to pay homage to it and to change it.

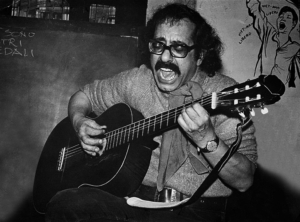

Armandino Liberti (Rome, 1970s), photo by Susanna Cerboni

LET’S START with the most material, concrete fact: the voice. In Una vita violenta (A Violent Life), Pier Paolo Pasolini describes a couple of times, briefly but precisely, the voices of his suburban characters: a “low, hoarse voice”, a “rough voice”. Armandino Liberti’s voice is precisely like that, “rough” both literally and, above all, metaphorically: Armandino Liberti’s oral, poetic, musical, political voice is not a voice that seeks to please, it is not a “beautiful voice” but a rough, harsh voice which, like other more famous rough voices, from Tom Waits to Bob Dylan, does not sing just for the sake of singing and to make life less bitter, but sings to tell us something and to give voice to all the bitterness generated by a society that exploits and marginalises him and those like him.

In fact, his best-known song, Noi de borgata, is an angry response to another Roman voice, rough but consoling. To Franco Califano, who in Semo gente de borgata sang “we’re better off than those who never eat”, as if foreshadowing today’s minister who claims that the poor eat better than the rich, Armandino Liberti responds by reminding us that his mother provides him with food by working as a servant in the homes of the rich; To Califano, who hoped for “tanti modi pe” sfonna’ (many ways to get out) by leaving the neighbourhood individually, Armandino Liberti responds by evoking a “popolana” (popular) justice that restores freedom and dignity to everyone together.

There is a classic African-American spiritual song about a train “bound for glory”, heading towards glory, towards paradise. This train, says the song, carries only the righteous and the saints, it does not carry thieves, whores, cheats… Bruce Springsteen takes hold of it and changes it: “this train carries saints and sinners, it carries losers and winners, it carries whores and gamblers” – there is room for everyone on the train to glory. There is room for everyone, workers and whores, rebels and pimps, even in Armandino Liberti’s poetic “train” travelling towards a proletarian utopia based on work: “The suburb then revives with work and freedom”.

Texts that recount the bitterness generated by an exploitative society

LET’S TAKE A CLOSER LOOK. Where does that strange expression, “s’arisana”, come from? It does not come from below, from the language of the slums; rather, it is the ironic popular appropriation of a word from the sociological and bureaucratic lexicon that thinks of the slums as a disease to be cured. Armandino Liberti reverses the meaning of the term: the slums are then healed, not as you say, with urban decorum and a few cosmetic adjustments, but as we say, with justice, work and freedom. Here too, be careful: it is not rehabilitation that makes the slums worthy of freedom, but freedom that will heal everyone, including thieves and pimps. When we are free, we will be restored.

Armandino Liberti came from the same world as Tommasino in Una vita violenta: “I’m a fanello and I’m from Pietralata”, and he was a communist, as Tommasino eventually becomes. He follows almost the same path: ‘I find myself face to face with life’, the trajectory of the street kid, petty theft, the “street hustlers” (Lenzetta in Una vita violenta), poverty, marginalisation, prison – until the vision of hope and redemption that Pasolini embodied in a “red rag, all soaked and stuffed”.

But while in Pasolini’s novels the suburbs are an excluded world, in his songs they are in relation/contrast and conflict with other institutions and other social strata.

HOWEVER, there is a difference. In Pasolini’s novels, the suburbs are an excluded world: the street kids roam the whole city, but the city never comes to the suburbs. In Armandino Liberti’s song, on the other hand, the suburbs are from the outset in relation – contrast, conflict, invasion, exclusion – with other institutions and other social strata: it is not a self-excluded world but a dominated world, the product of a network of power relations. It begins with the first verse: “and since the school kicked me out”; then continues with the propaganda “litany” of the media, the missionary intrusion of “priests, bizzoche and fiji de papà”: and the conflict between the suburbs and the world outside culminates in the last verse: the curse on “policemen, judges, lawyers”… / dogs loyal to the institutions’ to the “good, honest, cultured, refined people” who feed on the misery of the neighbourhood.

In this sense, it is worth returning to Gianni Borgna’s other suggestion: Armandino Liberti’s songs as “post-songs”. It is not entirely clear what Borgna meant, but there is no doubt that many of these compositions go beyond the song model we are used to. All in all, Noi de borgata is one of the simplest, most linear, verse after verse, as in traditional narrative ballads. In many other songs, however, there is no single idea, no single musical theme, no single voice, no single linguistic register; and it is not just a matter of the verse-bridge alternation of popular songs, but a play – a clash, a dialogue, an interweaving – of languages and voices. In a song like Omicidio bianco, the narrator’s voice, in essential, almost journalistic Italian, contrasts with the dialect of the child asking about his father who is not coming home (and the open, public space of the building site contrasts with the intimate space of a suburban kitchen). If we are talking about post-song, we should think rather of the Neapolitan sceneggiata, ready to transform itself into theatre: there is always dialogue, explicit as in Servo e padrone (Servant and Master), implicit in the dynamics between linguistic registers as a figure of class relations (and the sense of humour that runs through many of these songs, from the mockery of Dispettoso (Mischievous) to the self-irony of Mo’ la machina ce l’ho (Now I’ve got the car), also refers to theatre and masks.

I said that Noi de borgata is one of the least theatrical of Armandino Liberti’s songs. Yet, even here, there is more than one voice and subject: the maestro’s words, for example, are reproduced directly, as in a theatre script. But above all, in the last verse, Armandino Liberti addresses directly, in an implicit dialogue, the “first pillars” of this society – as if he had told his whole story to them, the implicit recipients, a silent chorus on the sidelines. Listening to these songs now, it is important to remember that they are at least half a century old and that many things have changed. And perhaps, looking each other in the face, we should ask ourselves who and where are those cultured and respectable people against whom the anger of a neighbourhood where that red rag no longer flies has become shapeless.

* One of the essays in the book/CD “Noi de borgata” (first release in the new series of the I giorni cantati collection produced by Circolo Gianni Bosio and the publisher Nota).

This post is also available in: Italian