Fausto Amodei, una chitarra non illibata ma innamorata

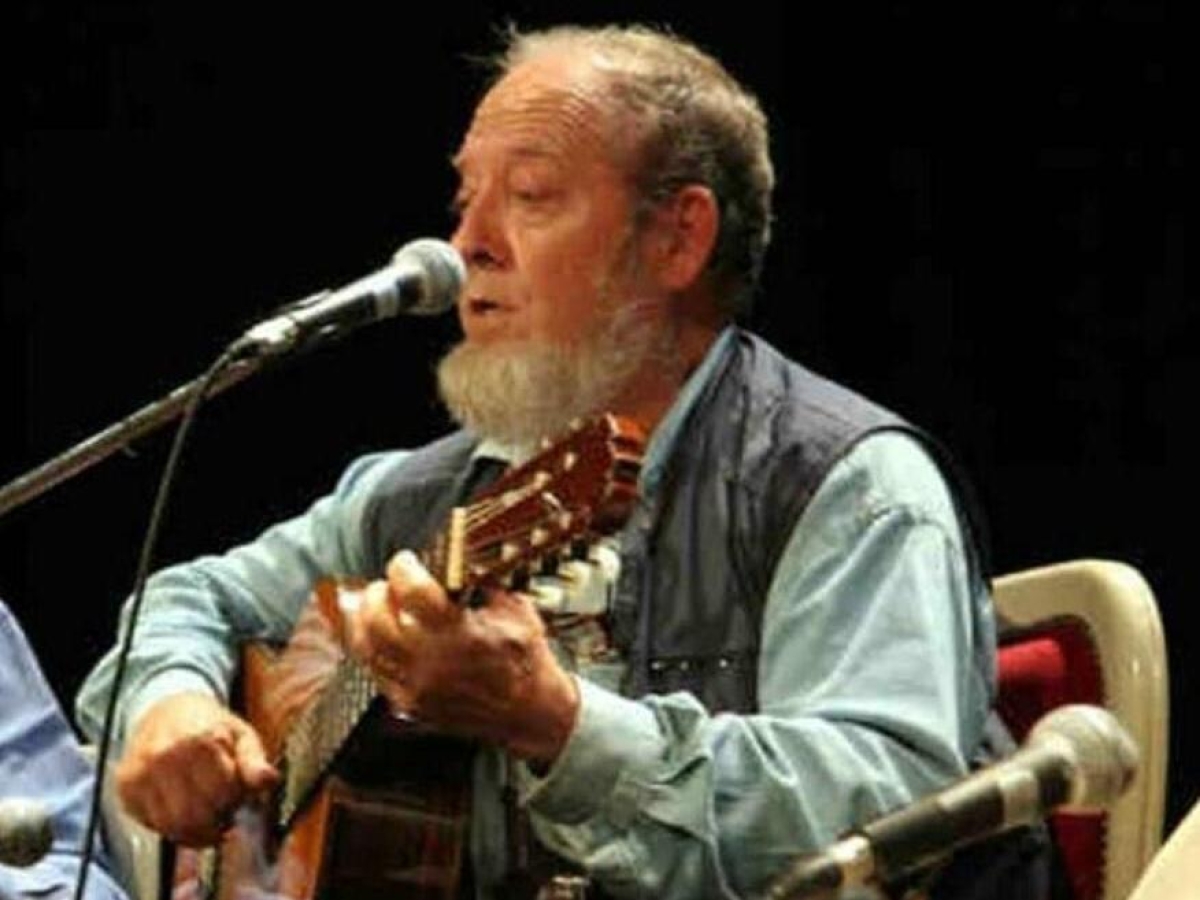

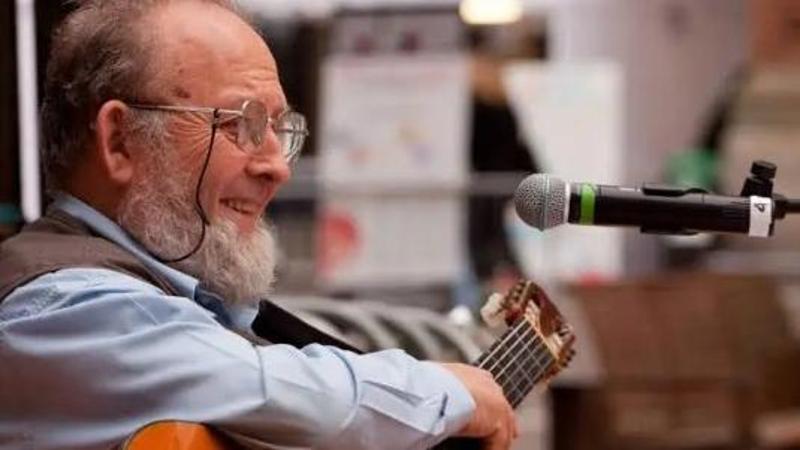

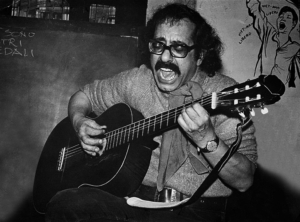

Aveva intitolato uno dei suoi dischi, nel 1965, “Canzoni didascaliche”. Uno di quei “Dischi del Sole” che sembravano dei 45 giri extended play e invece erano dei 33 in piccolo formato. Che modestia, che fair play, che autoironia. Certo, le canzoni di Fausto Amodei erano anche didascaliche, anzi quello fu un approccio stupefacente allo strumento della canzone, che forse è rimasto esclusivo suo. Basti citare Il tarlo, che partendo da un’aria della “Carmen” di Bizet era, in forma di deliziosa favoletta, sempre col sorriso sulle labbra, “una perfetta divulgazione del ‘Capitale’ di Marx”, così scrisse Umberto Eco; con puntualizzazioni persino tecniche intorno al sistema economico. O altre centrate quasi maniacalmente sugli aspetti finanziari della società: “Ero un consumatore”, “Uomini e soldi”, “Ninna nanna del capitale”, “II prezzo del mondo”. Immaginate come si possano cantare allegramente – e lui ci riusciva – concetti come l’inflazione, l’aumento dei prezzi, il consumismo, le speculazioni, i meccanismi di formazione della ricchezza, le fughe di capitali all’estero, le frodi commerciali, l’uomo valutato «non per quello che sa fare ma per quello che possiede», la concezione del plus-valore come «maltolto». Ma Fausto Amodei era anche ben altro. Era il contagio di un’indignazione popolare e l’inquietudine esistenziale, la satira esilarante e la puntigliosità del cesellare nei dettagli, da architetto, parole e melodie; e altro ancora. Quello che si dice un poeta. Se n’è andato a 91 anni, in un attimo, all’improvviso, ancora nella vitalità di un’esistenza certo placata ma ancora attiva e vigile. Con la sua barbetta e l’aria perenne di uno gnomo della foresta, pignolo e sornione, la voce incerta e petulante, apparentemente freddo e imperturbabile, è stato il grillo parlante della nostra canzone, praticamente il primo cantautore “politico” italiano dell’era

moderna, essendo stato tra i fondatori a Torino di quel movimento Cantacronache, a fine anni ’50, che per la prima volta innestò la canzone in un filone tematico strettamente connesso a concrete situazioni sociali, civili e appunto politiche. Quando i Cantacronache stampano il primo disco, addirittura un 78 giri che dire in edizione limitata è un eufemismo, diffuso con un altoparlante da un furgone durante la manifestazione della Cgil il 1° maggio 1958 a Torino, se una delle tre canzoni incise è “Dove vola l’avvoltoio” di Italo Calvino cantata in coro, le altre due sono interpretate proprio da Fausto: “La gelida manina o della coscienza politica”, che lui musica su testo di Guido De Maria, e “Viva la pace” di Michele Straniero e Sergio Liberovici. Il pacifismo fu un altro suo tema prediletto, si pensi anche al canto che contrassegnò la famosa prima marcia della pace Perugia-Assisi, il 24 settembre 1961, improvvisata sul momento da lui e Franco Fortini. Ma succede anche, inopinatamente, che fin dal ’59 una delle canzoni musicate da Amodei (su testo di Michele Straniero) raggiunge nientemeno che un’importante casa discografica e una sua promettente cantante, Ornella Vanoni, che tra le sue cosiddette “canzoni della mala” include, su uno dei primissimi dischi etichettati Ricordi, “La zolfara”, ispirata alla morte di 8 minatori in una solfatara siciliana. Da lì in avanti le canzoni di Amodei “cantautore” a tutti gli effetti – testi e musiche – non si contano. Una di esse diviene uno dei rari esempi di “canzone d’autore” entrata nel patrimonio popolare orale dei nostri tempi, ed è naturalmente quel grande canto di rivolta che è “Per i morti di Reggio Emilia”, originato dai luttuosi tumulti del 1960 contro il governo Tambroni appoggiato dall’estrema destra, tumulti che a Reggio lasciano sulla piazza 5 manifestanti.

“Zanzara”, il giornalino studentesco di Milano perseguito con una umiliante inchiesta giudiziaria perché aveva svolto un’inchiesta sulla sessualità fra i giovani (per la cronaca, il tribunale poi mandò assolti gli studenti, e il procuratore che li aveva accusati venne a sua volta indagato per collusioni con la mafia e sospeso dalla magistratura). Forse non si sa abbastanza che persino uno dei cavalli di battaglia del cabaret più surreale, lanciato in tv da Monica Vitti, è in buona parte suo: “I crauti”, scritta da un un gruppo di intellettuali buontemponi e buongustai di Torino (giornalisti, pittori, avvocati), tra cui anche Piero Angela (Francesco Guccini l’ha poi trasformata in “I fichi”, si vede che gli piacevano di più). E per tornare ai temi più politici, come non vedere, ahimè, l’attualità del nostro momento storico in “Non è finita a piazza Loreto?”. Peraltro Amodei ha imbottito la sua discografia anche di canzoni non sue, dunque lasciando un segno anche come interprete, sia alla voce che alla chitarra, e particolarmente nella riproposta del grande patrimonio di musica popolare che proprio Cantacronache prima e I Dischi del Sole dopo stavano riscoprendo e valorizzando. Cioè, tanto per dire, è anche dalla voce di Fausto che abbiamo potuto ritrovare documentate cose come “Trenta giorni di nave a vapore”, “Addio a Lugano”, “O Gorizia tu sia maledetta”, “La Comune di Parigi”, o altre della tradizione dialettale come “Jolicoeur”, “Baron Litron”, “Mia mama veul ch’i fila”… Non solo: Amodei recupera in un disco alcune canzoni di quello che reputava il nostro Brassens: l’avvocato astigiano Angelo Brofferio, personaggio del Risorgimento piemontese, illuminato ed anticlericale, giornalista, scrittore, uomo di teatro, nonché autore in dialetto di poesie e canzoni, musiche comprese, per lo più di satira politica, un po’ come il predecessore Ignazio Isler, abate settecentesco pure lui autore di canzoni piuttosto profane, attentamente studiato ed emulato dal nostro Fausto.

nostro Fausto.

Ma ad accomunare Brofferio allo stesso Amodei c’è anche qualcosa d’altro: il primo fu deputato della sinistra garibaldina al Parlamento Subalpino, fiero avversario di Cavour, sostenitore della democrazia; il nostro Fausto è stato negli anni ’60 deputato nelle file del PSIUP, e come per il suo modello ottocentesco non fu propriamente soddisfatto dell’esperienza, se la cantò polemicamente in una canzone, Il Parlamento, che non incise ma lasciò cantare a Leoncarlo Settimelli. Ora, non è un mistero che importanti cantautori taliani abbiamo riconosciuto il proprio debito nel repertorio dei Cantacronache e Amodei in particolare. Ecco una dichiarazione testuale di Francesco Guccini: “Fu dopo aver sentito i Cantacronache che cominciai a sforzarmi di comporre in maniera diversa. Questa gente mi è stata maestra. Penso in particolare a Fausto Amodei”. Al Club Tenco, quello presieduto dall’indimenticabile Amilcare Rambaldi, gli assegnammo uno dei primi Premi Tenco alla carriera, già nel 1975. Non poté essere presente subito, ma arrivò l’anno dopo, quando, incredibilmente, il “Tenco”, unica volta nella sua storia, passò in tv in diretta e in prima serata, comprese le inaudite canzoni politiche di Fausto Amodei! Ma Fausto non si fece notare solo sul palco, fu anche uno dei protagonisti del cosiddetto “dopoTenco”, ovvero delle cene seguite allo spettacolo, quando artisti e altri addetti ai lavori passano la notte a cantare insieme. Certosino versificatore qual è, Amodei seppe gareggiare a lungo nientemeno che con Francesco Guccini e Roberto Benigni nelle famose improvvisazioni di tradizione popolare in ottava rima. Conservo preziose registrazioni di quelle straordinarie sfide a tre. Amodei era reduce allora dall’album “L’ultima crociata”, che per la cronaca era

quella per il divorzio; da lì scattò ben un trentennio di silenzio discografico; ma evidentemente Fausto aveva ancora molte cose da dire contro chi detiene le leve delle nostre esistenze, tanto che nel 2005 se ne esce con un cd dal titolo sarcasticamente chiaro e tondo: “Per fortuna c’è il Cavaliere”. Ma non ce l’ha solo con lui, no: anche con i comunisti voltagabbana, con Bush quanto con Saddam, con i potenti corrotti di ogni parte politica, con la televisione, e così via. A pubblicarlo è Valter Colle per la sua etichetta Nota, e Valter sarà fino alla fine il suo affettuoso complice culturale e operativo. Nel luglio 2008, per esempio, lo porta a una grande serata di celebrazione dei 50 anni di Cantacronache a Cividale del Friuli, nell’ambito del Mittelfest allora diretto da Moni Ovadia. Poiché Valter mi chiamò a collaborare alla direzione artistica, pensai di invitare alcuni artisti di generazioni attuali a rappropriarsi di quel repertorio “vecchio” di mezzo secolo. La modernità di Amodei riesplose senza discussione quando, sull’indimenticabile palco allestito ai piedi della pietrosa Cava di Tarpezzo, vidi Caparezza interpretare “Il censore”, Frankie Hi nrg “Le cose vietate”, Alessio Lega “Il ratto della chitarra”, i Kosovni Odpadki “Ero un consumatore”, e l’incredibile ensemble Banda Osiris-Yo Yo Mundi-Moni Ovadia fare “Il tarlo” (che poi, lo stesso anno, Ovadia tornò a cantare al Premio Tenco). Per non parlare, in quella stessa occasione, di Giovanna Marini in Uomini e soldi o Gualtiero Bertelli nei “Morti di Reggio Emilia”. Non fu l’unica occasione, in quel 2008, che il Club Tenco tornò a incrociare Fausto Amodei. Il quale accettò di arrivare a Roma per cantare a una rassegna di canzone d’autore che curavo nel benemerito locale The Place, e fu poi presente a Sanremo per il “Tenco” di quell’anno, perché anche a Sanremo celebravamo il cinquantenario di Cantacronache, che combinammo con un omaggio all’appena scomparso Franco Lucà, anima del

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

leggendario FolkClub di Torino. Due eccellenti motivi per avere Fausto tra noi, a cui se ne aggiungeva un terzo, la presentazione del libro di Margherita Zorzi “Fausto Amodei, canzoni di satira e di rivolta” per le edizioni Zona. E proprio in occasione dell’uscita di questo libro, l’anno dopo ospitammo Amodei per un’intera giornata a lui dedicata nella mia città, Verona, e fu facile intitolarla “AmoDay”. Lo volli ancora a Verona nel 2012, in collaborazione con il Movimento Nonviolento, per un incontro pubblico con lui, nel teatro comunale Camploy, stavolta col titolo “E se la patria chiama…” Lui sempre affabile, generoso, ironico e autoironico. Un pizzico di Amodei rispuntò poi al Club Tenco nel 2015, con una chicca. Avevamo ideato una manifestazione collaterale, in quel caso sul tema dell’eros in canzone, col titolo “Pazze idee”, inserendo anche letture di testi di canzoni. Facendo ricerche presso quello che allora era il Crel di Torino (Centro Regionale Etnografico Linguistico, fondato proprio da Franco Lucà), avevo scovato una canzone di Amodei registrata in un suo live ma mai uscita su disco: “La diva”, storia di una ragazza piuttosto spregiudicata nell’approcciare il mondo dello spettacolo. Era giusta per il nostro tema e la svelammo al pubblico affidandola alla recitazione di Daria Anfelli e Massimiliano Antonelli. Nel 2021 arriva una sorpresa che finalmente appaga i “fans” (chiamiamoli così). Si era sempre saputo che Amodei non solo si era ispirato a Brassens, ma l’aveva anche tradotto, e finanche in piemontese, e giravano a questo proposito registrazioni più o meno clandestine. Ma mai un documento pubblico aveva ufficialmente sollevato il velo su questa ghiottoneria. Soltanto un pezzo, “Le tristezze di una donnina allegra”, era apparso in un album del ’73, rivelandosi subito come una chiara trasposizione, per ammissione dello stesso autore, di “La complainte des filles de joie”, ma non accreditata all’autore originale, chissà perché (problemi di diritti editoriali? pudore? caspita, non farò più in tempo a chiederglielo). Inoltre, alcune sue traduzioni erano state ospitate, su carta, in un paio di libri di Nanni

Svampa, suo omologo in questo tipo di operazione. È naturalmente Valter Colle a pubblicare finalmente su disco le sue versioni di Brassens, in registrazioni risalenti al 1990: 15 in piemontese e 7 in italiano. Operazione rinforzata nel 2023, sulla soglia dei suoi 90 anni, da un cd di altre traduzioni da Brassens, sempre per Nota, eseguite stavolta dal bravo Carlo Pestelli, concittadino e amico di Fausto. Anche come traduttore Fausto si conferma magistrale, linguisticamente e ritmicamente. E non solo dal francese: pochi sanno, ad esempio, che per un lavoro teatrale dedicato al vaudeville americano dalla bravissima e compianta Raffaella De Vita (napoletana trapiantata a Torino), a tempi di one-step, blues e boogie, Amodei curò – credo unico – le versioni in italiano di brani dal repertorio di mostri sacri del “pre-musical” come Al Jolson, Sophie Tucker, Jimmy Durante, Mae West e persino Bessie Smith. Ma le sorprese non erano finite. Fausto mi aveva parlato più volte di una sua creazione un po’ anomala, che gli stava molto a cuore: non canzoni ma una unitaria cantata per 4 voci e 6 strumenti, che aveva scritto ispirandosi al “Diario di trent’anni 1913-1943” di Camilla Ravera, cronistoria di una vita dedicata da protagonista alla genesi del Partito Comunista, sofferenze comprese come il confino impostole dal regime fascista. Ma sembrava difficile che qualcuno riuscisse ad allestirla, finché compare il demiurgo della situazione, e chi se non Giovanna Marini, che la concerta, la adatta e la dirige. Debutta a Roma il 21 giugno 2021 e Valter Colle la fissa su disco, immagino raggiante per dar voce in un sol colpo a quei suoi due grandi affetti, Giovanna e Fausto. Spero si sia capito che persona ci siamo persi con la sua scomparsa. Non però il patrimonio che ci ha lasciato, e la sua attualità. Il grande bersaglio di Amodei è stato sicuramente il potere: quello del bastone e della carota, del blando riformismo e della

Screenshot

repressione, coi suoi efficienti lacchè e i suoi benpensanti censori; il fascismo «che cambia colore ma è sempre quello, che sopra l’orbace ha messo la cravatta, che chiama sfollagente il manganello». Sulla carta la cosa potrebbe apparire noiosa se non fosse che il suo strumento principe è stato quello brillante della satira. Le sue ballate sono un concentrato velenoso ma anche comico di punture corrosive, non lasciano spazio a fronzoli o divagazioni, sono tutto succo. Di ironia sono pieni tutti i versi, l’ironia è in ogni concatenarsi di vocaboli, in ogni gioco di parole, in ogni rima accuratamente scelta, nella miniatura delle trovate umoristiche che si susseguono senza dar respiro. Quella di Amodei è una chitarra che – per usare le parole cantate da lui stesso – «canta senza paura dei versi un poco insolenti, in barba alla censura, contro i padroni e i potenti». Una chitarra che «canta senza pudore, senza badare agli offesi, anche argomenti d’amore, ma senza far sottintesi». Una chitarra «molto espansiva, non certo illibata, ma che concede i propri favori soltanto se innamorata».

recent years, several young musicians have given strength and value to the Friulian language in the regional music scene, exporting it beyond the borders of the Piccola Patria. Among these, Alvise Nodale, who has received prestigious national awards for his Gòtes, Massimo Silverio, and Nicole Coceancig, a singer-songwriter originally from Premariacco who now lives in Carnia and has an extraordinary voice, are certainly worth mentioning. I remember when I first met her, I was immediately struck by her energy and her unmistakable voice. One day, I told her an anecdote I had read in Johnny Cash’s official autobiography. The American artist says, “I am grateful for my gift: my mother always called my voice a gift”. This is Nicole’s distinctive feature, the gift of having a tone of voice that you may or may not like, but which remains unique, different from all the others you hear around you. But that’s not all, of course. Her poetics are marked by a firm conviction to spread messages of civil commitment. From the very beginning, the influence of Fabrizio De Andrè has been strongly felt in her musical writing, starting with “F”, her first work composed of nine songs in Italian. She has collaborated with numerous other artists, both in the musical and literary fields; one could say that Nicole is tireless. Every new artistic encounter is an enrichment and a new beginning for her. Her long collaboration with Leo Virgili has resulted in her new album, which received the prestigious Ciampi 2024 Award, published by Valter Colle‘s Nota label. The album, developed as a concept, tells the story of a young woman from Pakistan who arrives in Europe. As highlighted in the album presentation on the website

recent years, several young musicians have given strength and value to the Friulian language in the regional music scene, exporting it beyond the borders of the Piccola Patria. Among these, Alvise Nodale, who has received prestigious national awards for his Gòtes, Massimo Silverio, and Nicole Coceancig, a singer-songwriter originally from Premariacco who now lives in Carnia and has an extraordinary voice, are certainly worth mentioning. I remember when I first met her, I was immediately struck by her energy and her unmistakable voice. One day, I told her an anecdote I had read in Johnny Cash’s official autobiography. The American artist says, “I am grateful for my gift: my mother always called my voice a gift”. This is Nicole’s distinctive feature, the gift of having a tone of voice that you may or may not like, but which remains unique, different from all the others you hear around you. But that’s not all, of course. Her poetics are marked by a firm conviction to spread messages of civil commitment. From the very beginning, the influence of Fabrizio De Andrè has been strongly felt in her musical writing, starting with “F”, her first work composed of nine songs in Italian. She has collaborated with numerous other artists, both in the musical and literary fields; one could say that Nicole is tireless. Every new artistic encounter is an enrichment and a new beginning for her. Her long collaboration with Leo Virgili has resulted in her new album, which received the prestigious Ciampi 2024 Award, published by Valter Colle‘s Nota label. The album, developed as a concept, tells the story of a young woman from Pakistan who arrives in Europe. As highlighted in the album presentation on the website

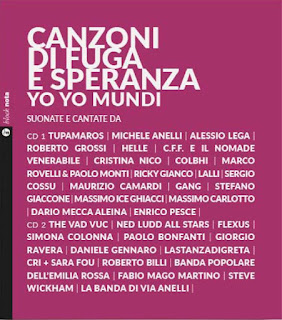

It was 1994 when a band from Acqui Terme released their first album, with a rather strong title: “La diserzione degli animali da circo” (The desertion of circus animals). We are, of course, talking about Yo Yo Mundi who, to celebrate over thirty years of career, are being honoured by important names in the Italian music scene. The artistic direction of the project is by Eugenio Merico, with Gianluca Spirito, Maurizio Camardi and the technical collaboration of Dario Mecca Aleina. The double album, with artwork by Ivano Anaclerio Antonazzo, contains a substantial 32-page booklet with an unpublished story by the late Giorgio Olmoti entitled “Lande Rumorose” (Noisy Lands). The first CD opens with a super folk version of “Freccia Vallona”, revisited by the ever-talented Tupamaros. The next track, “La storia e la memoria”, features heavy doses of electric guitar in Michele Anelli’s interpretation. ‘Chi ha portato quei fiori per Mara Cagol’ finds the right political-musical line in Alessio Lega (assisted by the trusty Rocco Marchi and Guido Baldoni). “Il silenzio che si sente” becomes even more pop and catchy thanks to the intertwining voices of Roberto Grossi and the excellent Helle. Passion and energy for “In novembre”, with C.F.F. and Nomade Venerabile; dirty and sharp “Domenica pomeriggio di pioggia”, with the talented Cristina Nico and the Colbhi collective. “Al Golgota”, on the other hand, is very evocative thanks to Marco Rovelli and the inseparable Paolo Monti. ‘Chiedilo alle nuvole’ is undoubtedly the highest and most intense moment of this work, with the great Ricky Gianco, the deep voice of Lalli, Sergio Cossu and Maurizio Camardi. The legendary Gang re-release “Tredici” (the version is the one contained in “La rossa primavera” from 2011), one of the most beautiful songs about the Resistance. Stefano Giaccone is also effective in revisiting “Il silenzio del mare”. Massimo Ghiacci (Modena City Ramblers) reinterprets “Ho visto cose che in solitaria” with Irish tones, while “Alla bellezza dei margini”, with the reciting voice of Massimo Carlotto and the musical finesse of Maurizio Camardi and Enrico Pesce, closes the first part. The unmistakable sounds of The Vad Vuc open the second disc with “Andeira”. “VCR” is a combat song with an Andean flavour, performed by the highly talented Ned Ludd All Stars (which, in addition to Gianluca Spirito, features Daniela Coccia – from Muro del Canto – on vocals). Flexus are enthralling in “Carovane”; Simona Colonna is as refined as ever in “Il respiro dell’universo”. “L’impazienza” is very energetic, performed by Giorgio Ravera (La Rosa Tatuata), accompanied by Paolo Bonfanti’s crackling electric guitar. “Fosbury” finds the right delicacy in Daniele Gennaro’s version. In “Evidenti tracce di felicità”, Lastanzadigreta happily combines singer-songwriter music with electronica, while Cri and Sara Fou give “Lettera di morte apparente” a very enveloping acoustic dimension. Roberto Billi fills “Ovunque si nasconda” with sunshine; “L’ultimo testimone” has dance echoes thanks to the Banda POPolare dell’Emilia Rossa. ‘Léngua ed ssu’ is embroidered with Fabio Martino’s accordion and Steve Wickham’s (Waterboys, Sinéad O’Connor, U2) prestigious violin. “Tè chi t’éi” is presented in a powerful live version, with Maurizio Camardi accompanied by La Banda di Via Anelli. This work is a true labour of love, where each artist has managed to personalise these songs, which have taken flight and truly become everyone’s. Projects like these comfort us and make us understand that nothing unites like music. Long live Yo Yo Mundi and their journey made up of stories, encounters, courage, memory, civic engagement and, above all, consistency.

It was 1994 when a band from Acqui Terme released their first album, with a rather strong title: “La diserzione degli animali da circo” (The desertion of circus animals). We are, of course, talking about Yo Yo Mundi who, to celebrate over thirty years of career, are being honoured by important names in the Italian music scene. The artistic direction of the project is by Eugenio Merico, with Gianluca Spirito, Maurizio Camardi and the technical collaboration of Dario Mecca Aleina. The double album, with artwork by Ivano Anaclerio Antonazzo, contains a substantial 32-page booklet with an unpublished story by the late Giorgio Olmoti entitled “Lande Rumorose” (Noisy Lands). The first CD opens with a super folk version of “Freccia Vallona”, revisited by the ever-talented Tupamaros. The next track, “La storia e la memoria”, features heavy doses of electric guitar in Michele Anelli’s interpretation. ‘Chi ha portato quei fiori per Mara Cagol’ finds the right political-musical line in Alessio Lega (assisted by the trusty Rocco Marchi and Guido Baldoni). “Il silenzio che si sente” becomes even more pop and catchy thanks to the intertwining voices of Roberto Grossi and the excellent Helle. Passion and energy for “In novembre”, with C.F.F. and Nomade Venerabile; dirty and sharp “Domenica pomeriggio di pioggia”, with the talented Cristina Nico and the Colbhi collective. “Al Golgota”, on the other hand, is very evocative thanks to Marco Rovelli and the inseparable Paolo Monti. ‘Chiedilo alle nuvole’ is undoubtedly the highest and most intense moment of this work, with the great Ricky Gianco, the deep voice of Lalli, Sergio Cossu and Maurizio Camardi. The legendary Gang re-release “Tredici” (the version is the one contained in “La rossa primavera” from 2011), one of the most beautiful songs about the Resistance. Stefano Giaccone is also effective in revisiting “Il silenzio del mare”. Massimo Ghiacci (Modena City Ramblers) reinterprets “Ho visto cose che in solitaria” with Irish tones, while “Alla bellezza dei margini”, with the reciting voice of Massimo Carlotto and the musical finesse of Maurizio Camardi and Enrico Pesce, closes the first part. The unmistakable sounds of The Vad Vuc open the second disc with “Andeira”. “VCR” is a combat song with an Andean flavour, performed by the highly talented Ned Ludd All Stars (which, in addition to Gianluca Spirito, features Daniela Coccia – from Muro del Canto – on vocals). Flexus are enthralling in “Carovane”; Simona Colonna is as refined as ever in “Il respiro dell’universo”. “L’impazienza” is very energetic, performed by Giorgio Ravera (La Rosa Tatuata), accompanied by Paolo Bonfanti’s crackling electric guitar. “Fosbury” finds the right delicacy in Daniele Gennaro’s version. In “Evidenti tracce di felicità”, Lastanzadigreta happily combines singer-songwriter music with electronica, while Cri and Sara Fou give “Lettera di morte apparente” a very enveloping acoustic dimension. Roberto Billi fills “Ovunque si nasconda” with sunshine; “L’ultimo testimone” has dance echoes thanks to the Banda POPolare dell’Emilia Rossa. ‘Léngua ed ssu’ is embroidered with Fabio Martino’s accordion and Steve Wickham’s (Waterboys, Sinéad O’Connor, U2) prestigious violin. “Tè chi t’éi” is presented in a powerful live version, with Maurizio Camardi accompanied by La Banda di Via Anelli. This work is a true labour of love, where each artist has managed to personalise these songs, which have taken flight and truly become everyone’s. Projects like these comfort us and make us understand that nothing unites like music. Long live Yo Yo Mundi and their journey made up of stories, encounters, courage, memory, civic engagement and, above all, consistency. Nicole Coceangig

Nicole Coceangig